On March 25, 1911, a fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory became the deadliest industrial disaster in New York City’s history and one of the most devastating in the nation. Within minutes, flames engulfed the top floors of the 10-story building. Drawn by a pillar of smoke and the sound of fire engines, horrified onlookers watched as scores of garment workers cried for help from the windows. They were trapped by the blaze, a collapsed fire escape, and locked doors. The fire ultimately claimed the lives of 146 workers. Read on for the full story of this chilling incident at manhattanname.

Background

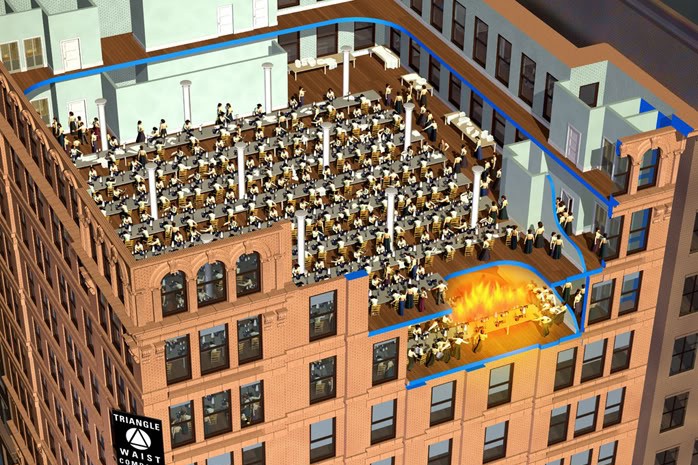

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was located on the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors of the Asch Building, which was later renamed the “Brown Building.” Today, the building is recognized as a National Historic Landmark and a New York City landmark. The factory produced popular women’s garments known as “shirtwaists” and typically employed about 500 workers. Their working conditions were grueling, forcing them to work long hours for wages as low as $15 per week.

The Fire

On Saturday, March 25, 1911, as the workday was ending, a fire broke out in a scrap bin on the 8th floor. The likely cause was a still-lit match or cigarette butt thrown into the bin, which was overflowing with highly flammable fabric cuttings. While smoking was officially forbidden, some workers secretly broke the rule, exhaling through their lapels to hide the smoke.

An accountant on the 8th floor was able to call and warn employees on the 10th floor, but with no fire alarm system, there was no way to reach the staff on the 9th floor. The building had four elevators with access to the factory floors, but only one was fully functional, and workers had to navigate a long, narrow hallway to reach it. There were two stairwells, but they offered no escape. One was locked from the outside, and the other opened inward—a common practice to prevent theft and unscheduled breaks. The inward-swinging door became impassable as the terrified crowd surged against it.

With no other way out, workers began jumping directly from the windows. The building lacked fire sprinklers, which could have stopped the blaze from spreading. A few people managed to save themselves by climbing to the roof or getting onto the elevators before they stopped working. Within three minutes of the fire starting, the stairs were unusable. The flimsy exterior fire escape twisted from the heat and buckled under the weight of too many people, collapsing and sending about 20 people to their deaths.

The fire department arrived quickly but was helpless to stop the tragedy. Their ladders reached only as high as the 7th floor. The growing number of bodies on the street below also hampered their approach. Elevator operators saved many before the heat warped the elevator rails. After that, some workers made a final, desperate attempt at survival by jumping down the empty shafts, trying to slide down the cables or land on top of the cars.

A large crowd gathered on the street, watching in horror as desperate workers jumped or fell to their deaths from the burning building. Often, a person’s hesitation was cut short when flames ignited their hair and clothing, causing them to fall as a living torch. The life nets held by firefighters ripped on impact. William Gunn Shepherd, a reporter covering the tragedy, described the sound of bodies hitting the pavement as a “ghastly thud,” a sound he would never forget.

The Victims: Mostly Immigrant Women

In total, 146 people died from burns, smoke inhalation, or the fall. The victims included 123 women and 23 men. Sixty-two people jumped or fell to their deaths from the windows. The vast majority were young Italian and Jewish immigrant women, with most aged between 14 and 23. The oldest victim was Providenza Panno, 43, while the youngest were Kate Leone and Rosaria “Sara” Maltese, both 14. Factory owners favored hiring immigrant women, who would accept low wages and were thought to be less likely to form unions. These workers were typically young, poor, had little to no education, and barely spoke English.

The victims’ bodies were taken to a makeshift morgue at the Charities Pier for friends and relatives to identify. They were buried in 16 different cemeteries. For a century, six victims remained unidentified. In 2011, historian Michael Hirsch finally identified them all after a four-year research effort using newspaper archives and other records.

Aftermath

The fire spurred major reforms, leading to the passage of New York State laws that dramatically improved factory safety standards. The tragedy also galvanized the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), which intensified its fight for better working conditions, including adequate breaks, safe temperatures, and proper ventilation in sweatshops.

The factory’s owners, Jewish immigrants Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, survived by fleeing to the roof. They were later indicted on charges of first and second-degree manslaughter. Their trial began on December 4, 1911, and lasted three weeks. With the details still fresh, over 150 witnesses testified, including dozens of survivors, firefighters, and police officers who described the factory’s layout and the fire’s horrific progression.

The jury acquitted Blanck and Harris of manslaughter. However, in a subsequent civil suit in 1913, they were found liable for wrongful death. The owners were ordered to pay $75 in compensation for each life lost. Meanwhile, their insurance company paid them about $400 per victim, a sum far greater than what the families received.

It is worth noting that Blanck and Harris had a history of suspicious factory fires. Rumors circulated that they practiced arson for the insurance money—a not-uncommon scheme in the early 20th century. While this wasn’t the cause of the 1911 fire, their negligence contributed to the tragedy. They had refused to install sprinkler systems, allegedly in case they ever needed to burn a factory for financial gain.

The last living survivor of the fire, Rose Freedman (born Rosenfeld), passed away in Beverly Hills, California, in 2001 at the age of 107. She had managed to escape by following the factory owners to the roof. The experience turned Freedman into a lifelong advocate for labor unions. Ultimately, the 1911 fire is remembered as one of the most shameful events in American industrial history, a tragedy defined by the fact that so many deaths could have been easily prevented.