New York City’s deep, salty rivers made it a popular port, but they also wreaked havoc on its drinking water. By the mid-18th century, Manhattan’s water was infamous for its scarcity and terrible taste – a problem stemming from human blunders made way back when Europeans first settled the borough. Read on to discover more about the fascinating history of Manhattan’s water supply at manhattanname.

The Early Days

The Lenape, the indigenous people, once inhabited the fertile lands they called “Manahatta,” meaning “hilly island”—what we now know as Manhattan. The land was teeming with forests and wildlife, sustained by numerous freshwater ponds and streams. For instance, the lower part of the island featured a 70-acre freshwater pond with sources stretching to the Hudson and East Rivers. After the Dutch arrived, the Lenape left some of their territory. The Dutch lived behind a wooden wall (now Wall Street) that spanned the island, built specifically to fend off native attacks that never materialized. In those days, people dug shallow wells and collected rainwater in cisterns.

In 1664, the English seized a large portion of the area, displacing the Dutch without a fight. Once settled, they began constructing wells that supplied the city with water for the next two centuries. However, the wells were far from ideal, suffering from poor sanitation and a lack of proper sewage systems. Waste often lay in the streets until New York finally passed a law requiring residents to dispose of their garbage by throwing it into the rivers.

Manhattan’s waterways suffered from industrial pollution and were also inadequate for fighting large-scale fires. For example, during the American Revolution, nearly a third of New York City burned to the ground on the night of September 21, 1776. After the revolution, the city battled outbreaks of yellow fever, characterized by a sudden onset, high fever, severe intoxication, liver damage with jaundice, and damage to kidneys and other organs. Contaminated waterways helped spread the disease, prompting New Yorkers to demand cleaner water from authorities.

The First “Water Supply” Company

The first proposed solution to the water problem came from Aaron Burr, a lawyer and politician famous for fatally shooting Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Along with his brother-in-law, Joseph Brown, Burr proposed creating a private company to provide the city with clean water. Burr actively sought support from both Federalists and Republicans. However, it later became clear that his motives weren’t about saving the populace, but rather his own financial gain. Burr’s true intentions were revealed after the passage of a law to supply New York with “pure and wholesome water.” One of its provisions allowed the newly formed Manhattan Company to do pretty much whatever it pleased.

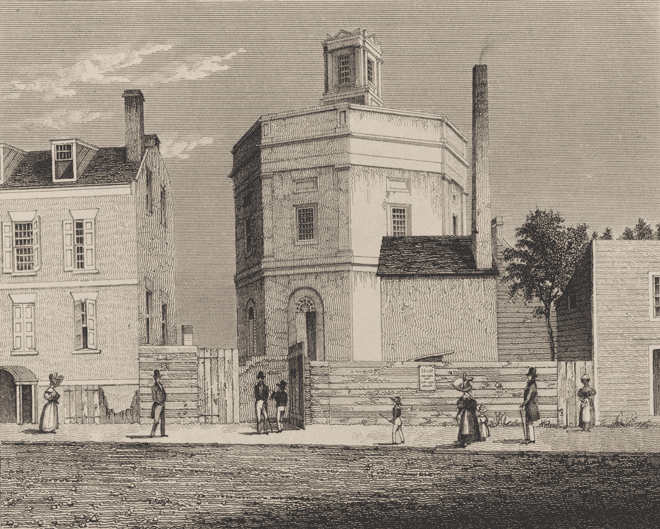

The company laid wooden pipes, ostensibly to achieve its goal of delivering clean water to the city. By the end of 1802, a total of 21 miles of pipes had been installed. Yet, the company largely neglected its water supply obligations, instead focusing on banking. Ultimately, Burr re-purposed the water supply venture into a bank, now known as JPMorgan Chase & Co., the largest bank holding company in the United States by assets.

Public Water Supply

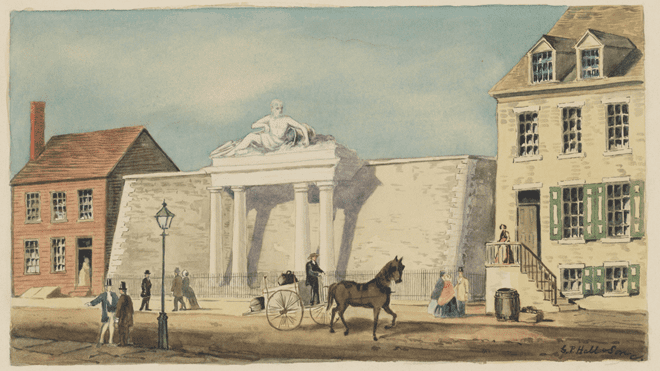

The city continued to decline due to the lack of quality water. In 1829, the city council decided to build a reservoir north of New York City. However, when it opened in 1831, it was primarily intended for firefighting rather than providing drinking water to the public. To combat the unpleasant taste, alcoholic beverages were often added to drinking water, which eventually fueled the temperance movement. In 1834, recovering from a cholera outbreak, New Yorkers began advocating for a public water supply. However, the authorities’ response was slow. Several fires in 1835, which depleted the 13th Street reservoir, sped up the decision-making process.

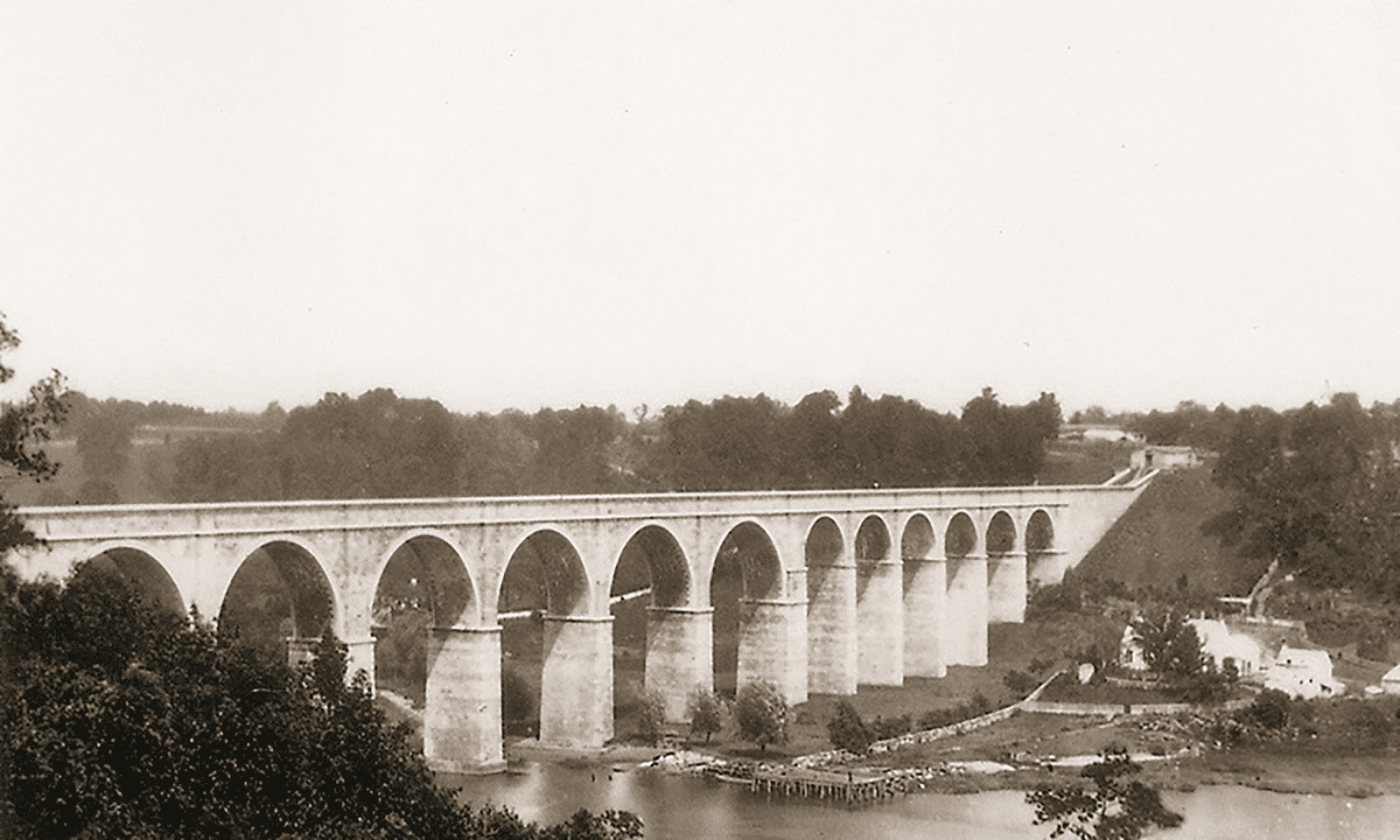

In 1837, construction finally began on the Croton Aqueduct, the first structure in New York City’s water supply system. This involved building a dam and drawing water from the Croton River in Westchester County. Water began flowing through the aqueduct in 1842, traveling 41 miles by gravity and reaching Manhattan in 22 hours. Wealthy New Yorkers gained bathtubs and running water in their private homes, while public baths opened for the masses. At the same time, the new water system had an unintended consequence: the reduction in residents drawing water from city wells led to a rise in groundwater levels. This caused many basements to flood. To solve this problem, the city built sewers on some residential streets. By 1852, 148 miles of sewers had been constructed.

The Croton Aqueduct Distribution Reservoir resembled an Egyptian pyramid and was located where Bryant Park and the main branch of the New York Public Library now stand in Manhattan. Despite its success, however, the aqueduct became outdated 40 years after its construction and could no longer meet the needs of the ever-growing population. In 1885, construction began nearby on the New Croton Aqueduct, which was put into operation five years later. This new structure had three times the capacity of the old aqueduct. Nevertheless, the old aqueduct remained in use until 1955.

The Croton Reservoir continued to supply New York with drinking water until 1940, when Parks Commissioner Robert Moses ordered it drained. The site was transformed into a lawn and a turtle pond. In 1987, the northernmost part was reopened to supply water to Ossining, a village in Westchester County.

The Modern System

In the 21st century, a combination of aqueducts, reservoirs, and tunnels ensures New York City’s fresh water supply. With its three main systems (Croton, Catskill, and Delaware), New York boasts one of the most extensive municipal water supply systems in the world. The water purification process here is simpler than in most other American cities, largely thanks to the high level of protection for its watersheds.

The unique terrain where the waterways are situated allows 95% of the water to flow into the system by gravity. The percentage of pumped water changes when its level in the reservoirs falls outside the normal range. From the Hillview Reservoir in Westchester County, water flows by gravity into three tunnels beneath New York City:

- Tunnel No. 1, completed in 1917. It runs from the Hillview Reservoir under the central Bronx, the Harlem River, the West Side, Midtown, and the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and under the East River to Brooklyn, where it connects with Tunnel No. 2.

- Tunnel No. 2, completed in 1935. It runs from the Hillview Reservoir under the central Bronx, the East River, and western Queens to Brooklyn, where it connects with Tunnel No. 1 and another tunnel extending to Staten Island. Upon its completion, it was the world’s longest large-diameter water tunnel.

- Tunnel No. 3 (partially completed), which begins near the Hillview Reservoir in Yonkers, then crosses Central Park in Manhattan to reach 5th Avenue at 78th Street. From there, it passes under the East River and Roosevelt Island to Astoria (Queens) and continues to Brooklyn.