In the colonial era and into the 19th century, New Yorkers kept cows right in the city, grazing them on public commons and squares. As the city grew, farmers from the surrounding areas supplied milk to vendors, who would deliver it door-to-door. They’d fill pitchers from buckets carried on yokes or in horse-drawn wagons. Because milk spoiled so quickly, it had to be brought into the city twice a day in the summer from farms in Brooklyn and the Bronx. As grazing lands were pushed further from the city and before refrigeration became available, it was impossible to transport milk without it spoiling. This forced a search for new methods to provide milk for the rapidly growing population, manhattanname.com.

The Pure Milk Movement

Beginning in the 1820s and 1830s, distillery owners created a market for the leftover grain mash from their operations, selling it as cattle feed. Farmers would rent stalls at the distilleries and feed their cows this slop at minimal cost. Although cows on this high-calorie diet produced more milk, the quality was low. The animals also didn’t get the vitamins and minerals they needed, and they were kept in filthy conditions. The watery, bluish slop was often mixed with additives like starch, plaster of Paris, and chalk to give it a more appealing color. While other cities had “swill dairies,” nowhere was this infamous brew as widespread as in New York.

This substandard milk soon gave rise to the Pure Milk Movement. One of its leaders was Robert Hartley, an activist likely more interested in uniting distillers for the temperance cause than in reducing the death rate from bad milk. Nevertheless, he played a vital role in bringing public attention to a problem that had become dire. By 1841, half of all children under the age of five in New York City were dying from typhoid or diarrhea-causing bacteria in the milk they drank. In 1875, a law was passed that prohibited the sale of milk from cows fed distillery byproducts. Decisive action by Dr. Samuel Percy of the Medical Academy and others led to the elimination of the swill dairies on Manhattan. Yet in 1904, the new city health commissioner found that 1,000 cows in Brooklyn were still being fed distillery slop.

The Certified Milk Movement was another response to the need for safe milk for infants. Initiated in 1891 by doctors from Harvard Medical School, the movement’s main goal was to ensure milk was produced and processed under strict controls. Doctors inspected not only the cows but also the animals’ living conditions, the buildings, the water on the dairy farms, and the milk collection and handling processes. By the early 1900s, numerous milk commissions had been established across the country. Dr. Henry Koplik opened the first milk dispensary to distribute pasteurized milk and teach mothers about infant hygiene.

In June 1883, the city’s first milk depot was opened at East Pier. This lab and recreation center housed a small plant for pasteurizing and bottling milk. Mothers and their children would come to purchase high-quality milk at an affordable price. By 1884, six more depots had opened in New York. In the early 1900s, milk stations modeled after the city’s certified farms opened in Brooklyn, Chicago, and Baltimore. Manhattanville residents were also active in the Pure Milk Movement. In 1910, socialite Ethel Gook and other society women founded the International Pure Milk League.

Dairy Farmers and Their Innovations

Soon, dairy farmers outside the city began advertising their clean, fresh country milk, actively competing with the swill dairies. One such farmer was Thompson Decker, who, after working as a cow milker and deliveryman on a Morrisania estate, started his own milk route in 1841. By the 1860s, Decker had bought 400 acres in North Salem, New York, and had 150 cows. He founded the company T. W. Decker & Sons and made history as the first New York milk dealer to use the railroad to deliver milk from Westchester, convincing the New York and Harlem Railroad to carry it by train.

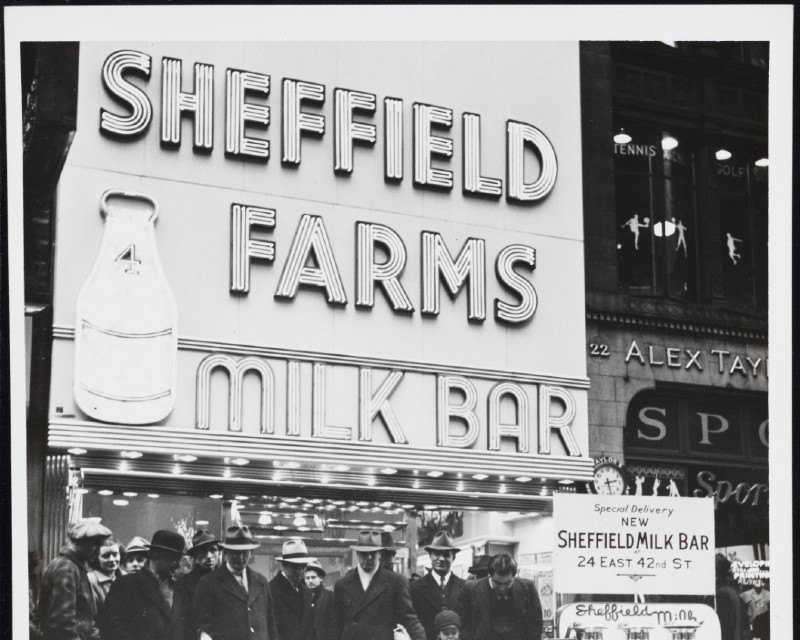

L. Halsey became interested in the dairy business when he was asked to help with butter deliveries. Through careful selection and breeding, the Sheffield herd of cows from Mavy produced excellent milk for making butter. Halsey began selling the butter in his spare time in New York and by 1880, he was fully dedicated to the business. His first innovation was designing a covered milk wagon to protect the milk from dust. In 1892, he installed the first U.S. pasteurization machine at his Sheffield Farms plant, which he had imported from Germany. In 1893, pasteurization was showcased at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The Milk Trains

By the mid-19th century, dairy farmers processed most of their milk into butter, which could be transported without spoiling and stored for a relatively long time. Drinking milk was consumed only locally until the advent of refrigeration. Special trains revolutionized milk delivery and gave farmers a new market for their product.

The first milk arrived in New York by ferry. The Erie Railroad was the first in the country to transport milk regularly. By 1843, the railway carried 4 million quarts of milk, and by 1884, that number had nearly doubled. By 1847, the Erie Railroad was running a regular milk train that delivered milk to Jersey City, where it was then ferried across the Hudson River to a special station in Lower Manhattan. In 1840, the New York and Harlem Railroad built a bridge across the Harlem River, providing the first direct freight connection to Manhattan, and by 1847, it was delivering 16 million quarts of milk to the city.

Milk was transported in 40-quart cans, with 300 cans fitting in a single car. Cooling was provided either by ice bunkers at both ends of the car or by ice placed directly on top of the cans. By 1926, tankers were introduced for this purpose. The cars were designed like Thermoses, so the milk wasn’t cooled, but rather kept at approximately the same temperature at which it was pumped. Later tanker models had two tanks that could be offloaded onto a truck at the station.

The Development of the Dairy Industry

Much milk was pasteurized on rural farms and arrived already bottled and packed in crates, but most of it was still pasteurized at plants in the city. By 1933, there were 12 pasteurization plants operating in Manhattan. Typically, milk arrived by train at 103rd Street at 11:00 p.m. and at the plant at midnight, ready for distribution by 2:00 a.m. From the plants, it was transported by vans or trucks to distribution stations or directly to customers on established routes.

In the early 20th century, many dairy companies, meatpackers, car dealerships, and auto parts and service centers located their businesses in the Manhattanville area due to the advantages of the West Side freight line. This ensured that fresh milk was delivered very quickly to Central and Lower Manhattan. By 1939, Borden’s and Sheffield Farms were part of the dairy industry’s “big three.” At the time, they controlled a third of the dairy business in and around New York City.

With the growth of the railroad and the implementation of innovations, the dairy industry continued to expand, providing New Yorkers with fresh, high-quality milk.