Once a cornerstone of New York City life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, public baths were magnificent municipal buildings that served a critical purpose for many residents. For those living in the city’s cramped, overcrowded tenements—often without running water—these baths were a lifeline. Today, scattered across Manhattan and other boroughs, you can still find buildings with two symmetrical entrances, one marked “Men” and the other “Women,” a subtle reminder of the city’s grand public baths. To learn more about their history and significance, visit manhattanname.com.

The First Municipal Bathhouse in NYC

New York’s first municipal bathhouse opened in the summer of 1870. It was essentially a pool submerged in the river, with fresh river water flowing through it. According to an 1871 New York Times article, it had a simple, house-like structure with a swimming area measuring 85 feet long and 65 feet wide. The bathhouse was equipped with 68 dressing rooms, offices, and additional rooms on an upper floor, which were lit by gas lamps for nighttime use. Just one year after it opened, the Department of Public Works reported the bathhouse was overflowing with visitors, especially on hot summer days.

A Construction Boom

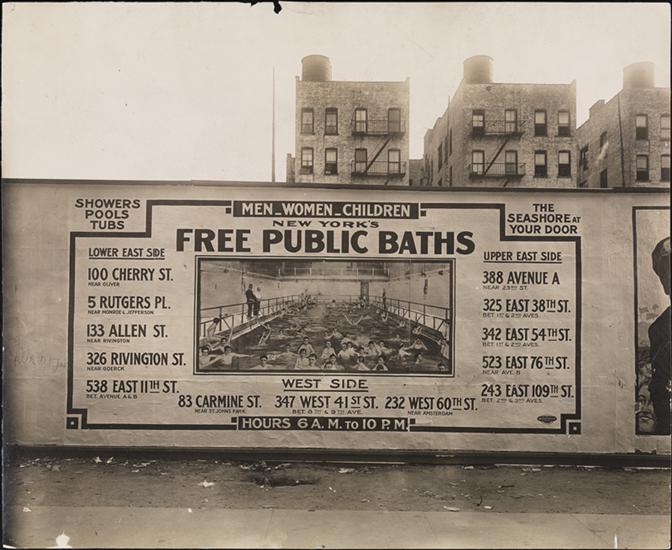

In 1895, a New York State law mandated that all cities build public bathhouses, sparking a construction boom in NYC. Baths were primarily built in densely populated, lower-income neighborhoods, and by the early 1900s, Manhattan alone had at least 14 of them. Many were stunning examples of Art Deco architecture, featuring decorative marble panels, colorful mosaics, intricate geometric patterns, glazed bricks, and graceful, winding balustrades.

Charitable organizations also played a huge role, building at least 12 bathhouses in Manhattan and Brooklyn to combat a public health crisis among tenement dwellers. Although building codes required bathrooms, they didn’t mandate showers or tubs, making it difficult for residents to maintain proper hygiene. This made them vulnerable to infections and diseases. To curb the spread of illness, city officials began building accessible public baths. While temporary floating baths appeared on the Hudson and East Rivers in the late 19th century, they were seasonal and many residents still lacked bathing facilities during the fall and winter.

The driving force behind the city’s bathhouses was Dr. Simon Baruch, a German immigrant who believed in the healing power of clean water. After moving to NYC in the 1880s, he began helping families in the tenements. At the time, the city’s population was soaring, and epidemics of typhoid and cholera were ravaging the Lower East Side. Baruch, inspired by Germany’s public bath system, returned there to study it, convinced it could help New Yorkers. He soon came back to NYC and began his campaign for a network of free public baths.

His efforts gained serious momentum in 1895 with the passage of the law requiring free bathhouses in cities with over 50,000 people. At the time, one survey found that in the Lower East Side, there was only one bathtub for every 79 families. For those without access, the People’s Baths at the corner of Centre and Grand Streets offered an alternative, charging just 5 cents for a bath, soap, and a towel.

In 1901, Baruch opened New York’s first indoor bathhouse, the Rivington St. Municipal Bath, at 326 Rivington Street. It featured indoor and outdoor pools, 67 showers, and 5 bathtubs. By 1911, Manhattan had 12 bathhouses, some with large swimming pools. One of the last to open in the 1920s still stands today at 35 West 134th Street.

Controversy and Danger

From the start, the city’s public baths were controversial. On one hand, they offered a much safer way to swim in the river during hot months compared to swimming in dangerous currents and the harbor. A study from the time revealed that in 1868, there was an average of one drowning per day. Additionally, political and charitable leaders saw the river baths as a way for the poor to stay clean.

Early river baths in Manhattan were incredibly popular. In their first year of operation in 1870, the two first bathhouses hosted around 4,500 visitors daily, and newspaper commentators urged the city to build more. However, some sources painted a different picture, giving the baths the reputation of “floating sewers,” with muddy, foul-smelling water.

Over the years, water pollution worsened. The rivers were filled with sewage, industrial waste, and blood from slaughterhouses. Yet, despite the growing pollution, river baths and swimming in the open river remained popular until several long-promised indoor baths finally opened in 1901. The Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor was instrumental in their construction and urged the Department of Health to close the outdoor river baths, citing serious concerns. In 1900, a conjunctivitis epidemic in Brooklyn was linked to a bathhouse located near a main sewer line. Furthermore, river baths were only open in the summer, and the city felt a responsibility to provide year-round, safe bathing for tenement residents. This was seen as not only promoting cleanliness but also preventing disease. The Department of Health recognized the severity of the problem. A few years later, in 1903, Health Commissioner Lederle advocated for keeping the baths open and relocating them to areas where the water was less contaminated.

When the Departments of Public Works and Health proposed shutting down the river baths permanently for sanitation reasons, it sparked an uproar among the poor. Many believed the city was eliminating the river baths to force people to use the indoor, fee-based ones. The Health Commissioner refuted this. After a final decision was made, Lederle clarified that the river baths would continue to operate, stating that it was unfair to deprive lower-class citizens of their only bathing option.

The End of an Era

In 1914, authorities began to build enclosed floating baths filled with purified, filtered water. Still, a debate raged over funding for the river baths. Manhattan Borough President Marks publicly clashed with the City Inspector, advocating for municipal funding and insisting the floating baths were still popular.

Attendance at the baths only began to wane after beach swimming became more accessible. As late as 1932, seven floating bathhouses were still in use in NYC as public health experts and city officials fought to keep people from swimming in the rivers due to pollution and frequent drownings. Many officials were also simply disgusted by the public nudity that they had been trying to eliminate for over 60 years. In 1937–38, the Department of Parks launched a program to educate children about the dangers of swimming in the East River. During this same period, the Department of Parks made a final attempt to save the floating baths by securing them to barges on the East and Hudson Rivers at 96th Street.

Just a couple of decades after many bathhouses opened, most fell out of favor. Innovations in home plumbing and other sanitation advancements made public bathhouses obsolete. Nearly all were permanently decommissioned after World War II, raising the question of what to do with these still-relatively-new, large municipal buildings. Some were repurposed as public recreational pools, a simple conversion since many of the bathing facilities could be reused and the buildings were already equipped with plumbing infrastructure. Today, around 10 former public bathhouse buildings remain in Manhattan.