New York City is home to an estimated 1,250 plant species. These plants face numerous threats, including pollution, climate change, and competition from invasive species. While New York City might seem like a concrete jungle, about 40% of its area is actually dedicated to green spaces. This diverse range of habitats—from tree-lined city streets to forests and salt marshes—provides food and shelter for a wealth of wildlife. Here, manhattanname explores some of the most common plants you’ll find in Manhattan.

Norway Maple

The Norway Maple (Acer platanoides) is native to Europe and Western Asia. It’s a tall tree, reaching heights of 65 to 100 feet (20 to 30 meters), with bright green, lobed leaves that turn yellow or red in the fall. In the U.S., the Norway Maple is grown as an ornamental shade tree. However, it’s considered an invasive species, meaning it was introduced from abroad and spreads naturally or with human help. Despite their benefits, these non-native trees pose a significant threat to the flora and fauna of certain ecosystems because they can outcompete native species. For instance, Norway Maples produce a large amount of seeds that are carried by the wind to nearby natural areas, creating problems for native plants.

The first documented import of the Norway Maple to North America was in 1756, when John Bartram received seedlings from England and began cultivating the species in his Philadelphia garden and nursery. Soon after, Norway Maples appeared in nursery catalogs in New York and California. In Manhattan, you can spot Norway Maples in parks and gardens. It’s a popular choice for planting due to its tall trunk and tolerance for compacted soil, limited root space, shade, and air pollution. Varieties with dark purple leaves are often cultivated in residential areas. However, the Norway Maple is vulnerable to fungal diseases and is rarely grown commercially because gray squirrels enjoy stripping its bark.

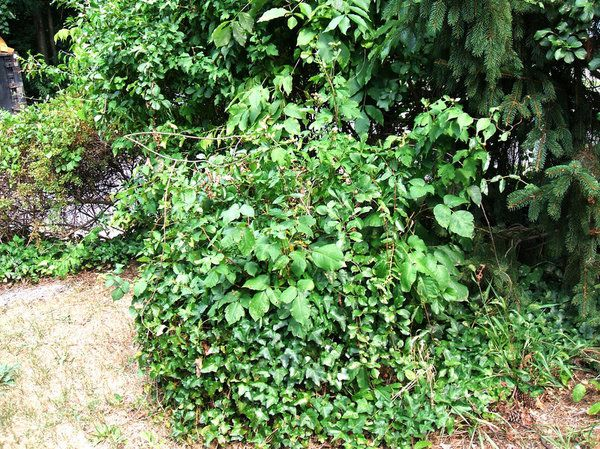

Poison Ivy

This plant is a well-known weed that can cause an unpleasant rash upon contact. Furthermore, it can lead to contact dermatitis caused by urushiol, characterized by redness, swelling, blisters, and sometimes scarring. However, many animals feed on poison ivy, and its seeds are a favorite among birds. In the fall, its leaves turn a vibrant red. The plant has numerous subspecies and can grow as both vines and shrubs. Despite its common name, it is not a true ivy. In Manhattan, this weed is most often found along roadsides, in wooded areas, wetlands, parks, and yards.

London Plane Tree

This sturdy tree, growing to heights of 65–130 feet (20–40 meters), excels in urban environments due to its tolerance for air pollution and compacted soil. In the spring, the London Plane produces inconspicuous red flowers. After wind pollination, these develop into spiky fruit balls containing a dense cluster of seeds with stiff hairs. The fruits slowly disintegrate throughout the winter, releasing the seeds. Finches, goldfinches, and squirrels are often seen in these trees.

The London Plane is believed to be a hybrid of the Oriental Plane and the American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis). Both parent species were once introduced to Britain, where, according to one theory, this new hybrid originated. This tree, valued for its ornamental qualities, can be seen in Manhattan’s parks and along its roadsides. You’ll recognize it by its distinctive mottled bark and large canopy.

Golden Pothos (Devil’s Ivy)

Golden Pothos (Epipremnum aureum) is commonly known as ‘Devil’s Ivy’ because it’s hard to kill and can thrive even in low-light conditions. Additionally, Golden Pothos produces a poisonous sap that is toxic to dogs and cats. This plant is prevalent in Australia, Asia, and the West Indies, and originates from the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific Ocean.

In Manhattan, Golden Pothos is grown in yards and gardens because it climbs beautifully, is adaptable, and requires minimal care. It’s often used as a natural fence or screen. You can also see it in hanging baskets and at the base of tree trunks. Furthermore, it’s a popular houseplant. Too much shade can cause its variegated leaves to lose their characteristic pattern and turn solid green. Moving the Golden Pothos to a brighter spot usually restores the variegation. However, overly pale leaves indicate the plant is receiving too much direct sunlight.

American Pokeweed

Although its berries look juicy and tempting, the fruits of this flowering plant are toxic. American Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) is considered a pest but is often grown for ornamental purposes. North America has two native species of pokeweed: one is widespread across most of the continent, and the other is found in California and the southwestern U.S. American Pokeweed typically reaches a height of 6 to 10 feet (1.8–3 meters).

Its leaves are thin and green. The flower clusters can be white, green, pink, or purple. Young leaves and stems, if prepared correctly, are edible and provide protein, fat, and carbohydrates. However, this should only be attempted by experts, as the plant is generally poisonous and, in rare cases, can even be fatal. In Manhattan, American Pokeweed is most commonly found at forest edges, near fences, under power lines, in pastures and old fields, in hedgerows, and other similar locations.

Virginia Creeper

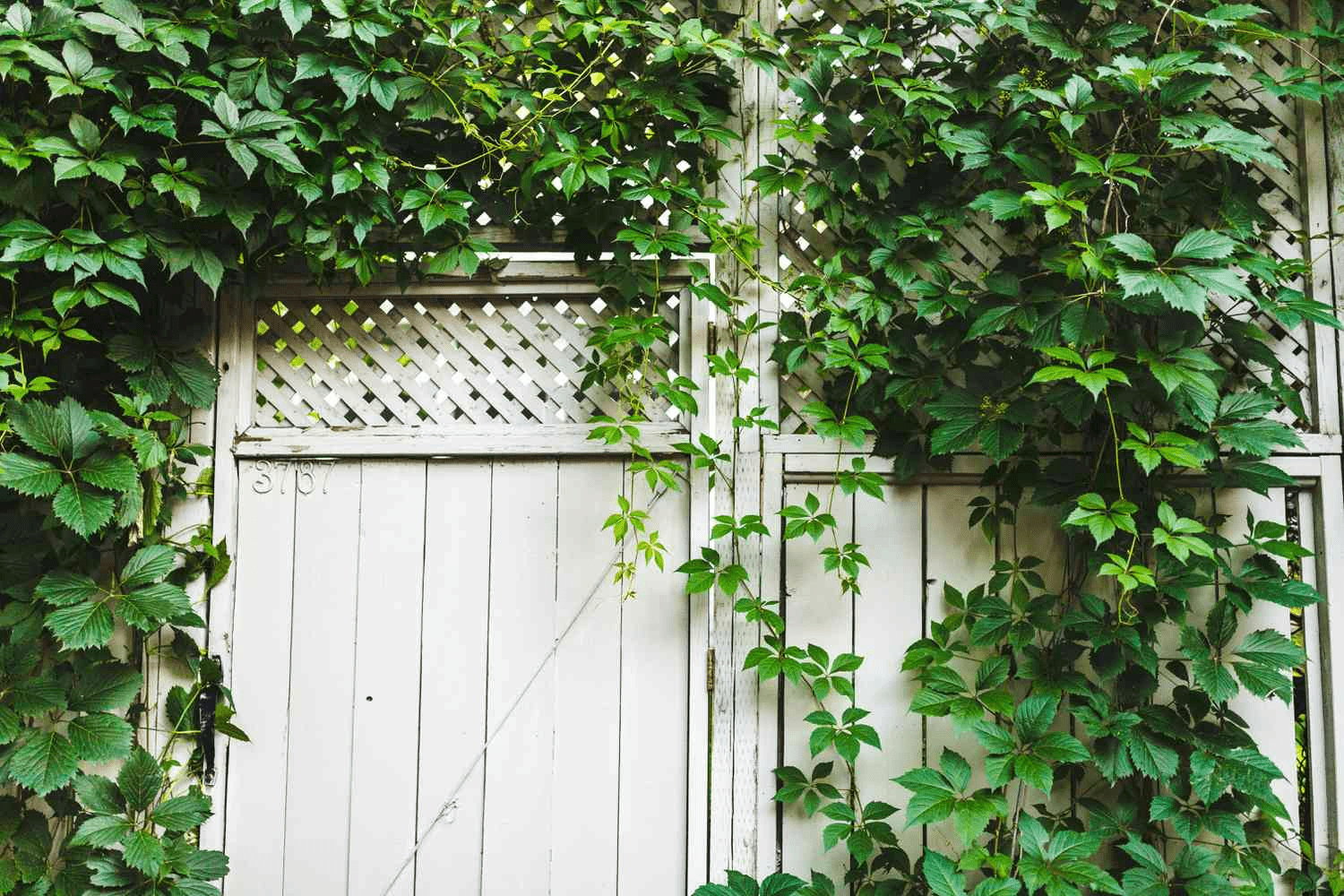

This North American woody vine from the grape family (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) is known for its fragrant flowers, ornamental blue berries, and leaves that turn a brilliant crimson in the fall. Using small, forked tendrils with adhesive pads, the plant clings firmly to almost any surface. It can cover large areas, providing shelter and food for wildlife.

In Manhattan, Virginia Creeper is used as a climbing vine and a groundcover plant. Its leaves create a lush green ‘carpet’ over any surface before turning vibrant colors in the autumn. The plant tolerates most soil types and climatic conditions.

Bigleaf Hydrangea

The Bigleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla) is a shrub native to Japan, known for its lush, oval, colorful flower clusters. There are two main types: ‘mopheads’ with large, round, sterile flower clusters, and ‘lacecaps’ with small, round, fertile flowers in the center and sterile flowers on the outside of each cluster. Depending on soil acidity, the flowers can change color from pink to blue.

In Manhattan, you’ll primarily see Bigleaf Hydrangeas in gardens and yards. The plant prefers sunlight, but in hot climates, it does best with morning sun or late afternoon sun. In cooler climates, it can tolerate full sun all day. On very hot days, it might wilt slightly, but this isn’t a major issue if it’s watered regularly. Bigleaf Hydrangeas have large leaves that transpire a lot of water, which needs to be replenished by rain or irrigation. During its blooming period and in hot weather, it’s best to water the plant 1–3 times a week.